If you want to know why computer games are the way they are today, you need to study the games of the past. See how nearly 70 years of games history has shaped today’s games.

I have a degree in modern history from Pembroke College, Oxford and history continues to be a hobby of mine. So it made sense to combine my interest in history with my professional interest in computer games.

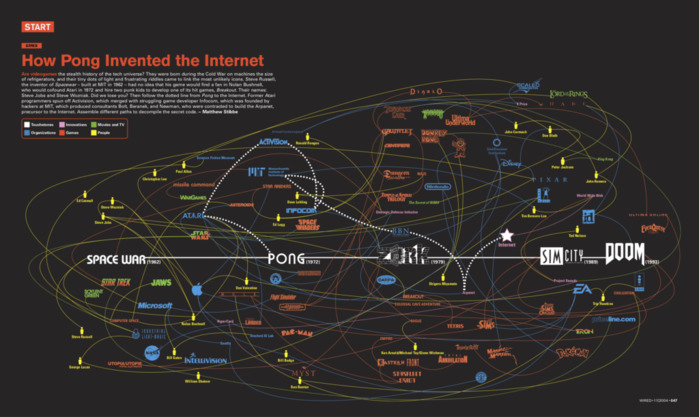

This is a transcript of a speech I gave on the history of computer games at the Game Developers Conference Europe in the summer of 2001. It is also the basis of this infographic I helped to create for Wired.

I originally published this article on my own website, Stibbe.net, and I have lightly updated it for republication as a single post here on GeekBoss.

Introduction to the history of computer games

I want to see where today’s genres came from and to look for anything that can help us make better games today.

To get ready, I replayed all the games. They’re all available free on the Internet: just follow the links on the following pages.

Although I’ve tried to use my historical training and my practical experience as a journalist, the list and the treatment are still highly subjective. This is because all the games have influenced me personally at different times in my life. To this extent, it is also a brief history of Matthew Stibbe.

Pong

Do you remember how old you were when you first saw this screen? In my case, I was six and, since my father didn’t want a TV, I had to go to a friends house to play it.

Although it's my starting point, Pong is not the first ever video game:

In the beginning (1958!) there was “Tennis for Two” by Willy Higginbotham at the Brookhaven National Laboratory. “Tennis for Two” begat the Magnavox Odyssey. In 1972 an ambitious young, Silicon valley entrepreneur saw an early version. This man was Nolan Bushnell. It inspired him to start Atari, which was the first dedicated video game company.

Bat and ball

He assigned the company’s first engineer, Al Alcorn, to build a simple bat and ball game called…

…Pong

So called because someone had trademarked the name Ping Pong. Certainly not the last time that this problem has occurred. At least it wasn’t Pong.com. In England it had a different name, because “Pong” had smelly connotations over here.

Pong was a very simple game with very simple instructions: “Avoid missing ball for high score” which, by the way, is a pretty good rule for life. This was really the beauty of the game. Remember – nobody even knew how to play a videogame in 1972 apart from a bunch of PhD students at MIT, and there were no arcades so the first video games were in bars. You REALLY needed a simple game!

The following passage, taken from “Zap! The Rise and Fall of Atari,” is an account of Pong’s first night at Andy Capp’s bar in Sunnyvale:

“One of the regulars approached the Pong game inquisitively and studied the ball bouncing silently around the screen as if in a vacuum. A friend joined him. One of [them] inserted a quarter. There was a beep. The game had begun. They watched dumbfoundedly as the ball appeared alternately on one side of the screen and then disappeared on the other. Each time it did the score changed. The score was 3-3 when one player tried the knob controlling the paddle at his end of the screen. The score was 5-4, his favor, when his paddle made contact with the ball. There was a beautifully resonant “pong” sound, and the ball bounced back to the other side of the screen. 6-4. At 8-4 the second player figured out how to use his paddle. Seven quarters later they were having extended volleys, and the constant pong noise was attracting the curiosity of others at the bar. Before closing, everybody in the bar had played the game. The next day people were lined up outside Andy Capp’s at 10 A.M. to play Pong.”

Home Pong

Then came Home Pong in 1974 and the Atari VCS in 1977. The first cross-platform development and the first coin-op conversion (but not the last!). There were very many clones of the game, each offering more features, such as colour, or better prices and so on. This was the first rush of me-too’s.

What’s great about Pong (and what is different between Pong and Bushnell’s Space War clone):

- It’s about as simple as it could get. Maybe a logician could define a simpler game but I can’t.

- You can see how it works by watching the demo mode. The instructions are redundant.

- It works by analogy to something in the real world.

- Sound (one sample: “Pong”) is critical to the appeal, gameplay and psychological addictiveness.

- Its scoring system generated competition and interaction between players

- Novelty generated word of mouth viral marketing: “hey look at this”

- It didn’t invent anything: it combined new technology, gameplay and accessibility in a way that didn’t exist before.

- A new business model: instead of buying a $120,000 PDP-1 to play space war at $300 per hour, you could play for 25c.

Interestingly, Pong was not Nolan Bushnell’s first-ever video game. His first game was not a success. He called it Computer Space, and this was the inspiration: Spacewar!

Spacewar!

What astounds me is that this first-ever computer game has so many features of so-called modern games. To put it into a historical context: this game was conceived in 1961. That’s 17 years after the end of WWII, before manned spaceflight and the same year Ivan Sutherland invented “Sketchpad” the first interactive graphics program and about the same time as the first stirrings of the ARPAnet.

Besides Nolan Bushnell, another early addict was Alan Kay, who invented the WIMP interface at Xerox Parc. He said: “The game of Spacewar blossoms spontaneously wherever there is a graphics display connected to a computer.”

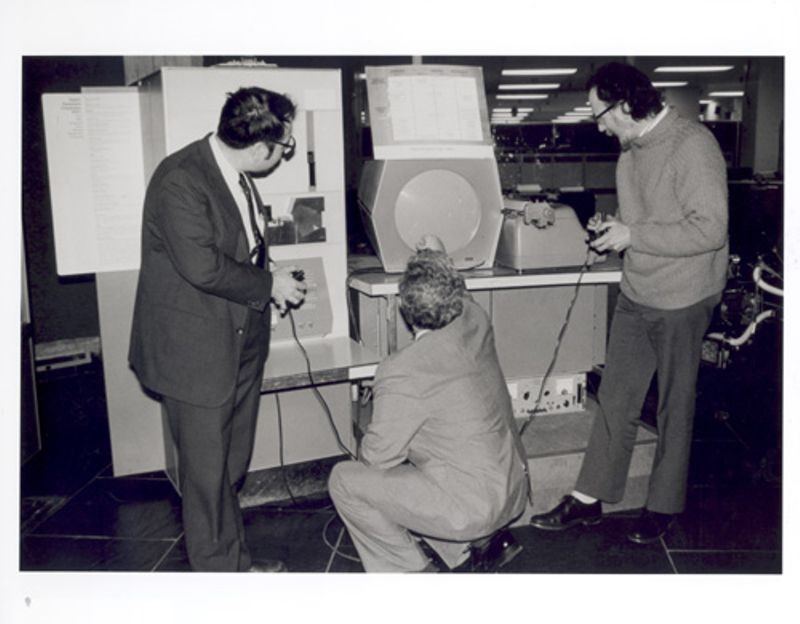

I believe this is a picture of some of the creators, who were Stephen Russell, Peter Samson, Dan Edwards, and Martin Graetz, actually playing the game.

Living computer history

(Long after I gave this lecture, I was visiting the Computer History Museum in Silicon Valley and the docent for our little tour was none other than Steve Russell. It was like being given a tour around a NASA museum by Neil Armstrong. Unbelievable. He was such a gent.)

The story of its creation is familiar to all of us. They wanted to produce a demo that would show off their new hardware, in this case the new vector graphic display. Martin Graetz wrote about it in an article for Creative Computing in 1981. He said:

A good demonstration program ought to satisfy three criteria:

- It should demonstrate as many of the computer’s resources as possible, and tax those resources to the limit;

- Within a consistent framework, it should be interesting, which means every run should be different;

- It should involve the onlooker in a pleasurable and active way — in short, it should be a game.

This seems to be a pretty good starting point for any game today.

Real-time HMI

They weren’t just inventing the video game, they were inventing the controls too. At first, it was played with the toggle switches on the actual mainframe. Graetz again: “At the very least, a jittery player could miss the torpedo switch and hit the start lever, obliterating the universe in one big anti-bang.” Later they raided the university model train society and got some analogue controllers they could use instead.

Another nice story that resonates with modern designers is ‘feature creep’: Another student had invented the “Expensive Planetarium” which used actual planetary data above Boston. They incorporated this into the game to provide the background of the screen, and by flashing each point of light, the stars can be made to glow at the correct level of brightness.

The game itself runs to 9kb of memory and 40 pages of listings.

Rolling Stone

This may have been the first and last time computer games were genuinely hip: when the now-famous Annie Liebowitz photographed the winner of the ‘Intergalactic Spacewar Olympics’ for Rolling Stone magazine in December 1972. This was ten years before the PC and five years before the Atari VCS. It sums up the historical significance of Spacewar! better than I can. I quote: “Yet Spacewar, if anyone cared to notice, was a flawless crystal ball of things to come in computer science and computer use:”

- It was intensely interactive in real time with the computer.

- It encouraged new programming by the user.

- It bonded human and machine through a responsive broadband interface of live graphics display.

- It served primarily as a communication device between humans.

- It was a game.

- It functioned best on, stand-alone equipment (and diarupted multiple-user equipment).

- It served human interest, not machine. (Spacewar is trivial to a computer.)

- It was delightful

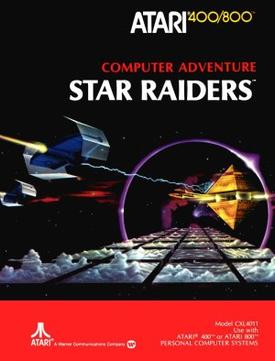

Star Raiders

In 1979 Atari launched their 400 and 800 series home computers. One hardware engineer, Doug Neubauer, had been working in his spare time on a game that synthesised the frenetic action of Spacewar! …

…and the more strategic elements of the text-only Star Trek-style games that were popular at the time.

Star Raiders was the first game for the new Atari computers and showed off their capabilities. It was the first real-time 3D game. It looks and plays a lot like Elite or Wing Commander but without the trading aspect or the FMV. In fact, it was sold on an 8K ROM cartridge.

Real-time almost-3D

Some familiar themes emerge from the development. I am quoting from an interview with Neubauer:

- Developing at the cutting edge: “The routines in Star Raiders are total hacks! It was the first game to use 3-D algorithms, and the ones I came up with were terrible. They worked, but were slow.”

- Balancing: “When I was doing the final touch-up on Star Raiders, a lot of people at Atari were playing the game. This allowed me to fine-tune the scoring algorithm.”

This is pretty much where I start following games. I saw Star Raiders at a computer show in the Novotel out in Earl’s Court. It must have been 1980 or 1981 and I was mesmerised by it. I had an Atari 400 a few years later and now I have an Atari 800. I still play this game now and again.

The next game, though it came out five years later is much better known…

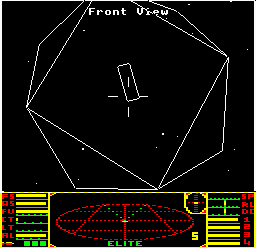

Elite

Elite.

Hands up if you played this BBC Micro computer game!

The game was written by David Braben and Ian Bell starting in 1982 and launched in September 1984 by Acornsoft.

I played this a lot at school. Curiously, on the Internet you can download an unpublished Atari version of the game which makes an interesting comparison to Star Raiders.

Besides being the source of much nostalgia – it is the geek equivalent of a first kiss for many of us – it needs some scrutiny as a game. I interviewed hundreds of programmers at IG and I ask many of them what their favourite game was: the most popular was Elite. Why? People usually cited the limitlessness of the universe and the open-endedness of the game play. They liked the illusion – and it was much more imaginary than real – that they could go be a pirate or a trader or whatever. Searching my own memories hard and replaying it, I think the main thing was the endless blasting. Certainly, it was banned at my school after all the space bars stopped working.

Elite on everything

There was a raft of ports and several disappointing sequels. Games like Wing Commander never really lived up to the legacy left by Elite and the genre seems to have disappeared with only Microsoft Star Lancer carrying the flag forward. I think this is a forgotten genre that is worthy of re-exploring.

- Play Elite in your browser (a very good emulation)

- Ian Bell’s homepage. He has lots of different versions listed.

- Frontier (David Braben’s company)

- BBC Emulator to play the game and a list of downloadable games are here.

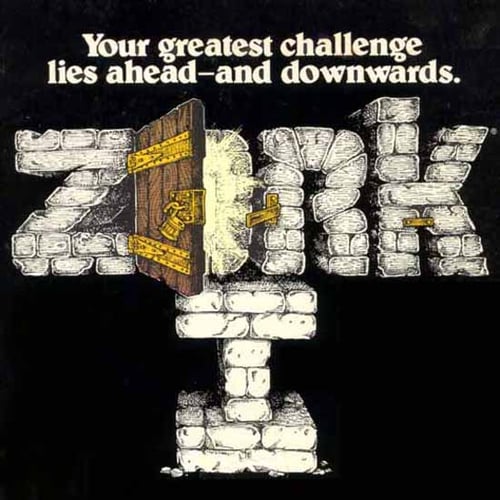

Zork

You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door. There is a small mailbox here.

>

In early 1977, Adventure swept the ARPAnet. Willie Crowther was the original author, but Don Woods greatly expanded the game and unleashed it on an unsuspecting network. When Adventure arrived at MIT, the reaction was typical: after everybody spent a lot of time doing nothing but solving the game (it’s estimated that Adventure set the entire computer industry back two weeks), the true lunatics began to think about how they could do it better.

David Lebling, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels and Tim Anderson set to work on their first text adventure. Dungeon was completed in June 1977. Infocom was started and in 1980, Zork: The Great Underground Empire Parts I and II were released. These first two Zork games were an instant hit and sold 1m units across all platforms.

Zork Infinity

I had read about Zork in Byte magazine and I played a later Infocom adventure, Planetfall, from start to finish. Came with all kinds of little doodads in the box – postcards from outer space and a Stellar Patrol ID card (which I still have somewhere).

As with other games here, this is something that came out of academia.

- Used emotion, character, humour – I remember being very moved when Floyd sacrificed himself to save me in Planetfall.

- A simple UI (complex underneath)

- But failed when expectations grew – e.g. Shogun in 1986 (which I also played from start to finish) was the last true Infocom game and hadn’t really developed at all in terms of technology.

The original Zork games used a novelist’s techniques of storytelling and imagination. They translated pretty well to a text-only game. When Return to Zork was released by Activision many years after the original as an “interactive movie” it showed how badly the techniques of film and TV translated to computers.

- Play Zork in your browser

- Play Zork in Slack. (Coincidentally, this is how the Geek Boss site got its name. I set this up for Slack at my company, Articulate Marketing, as a bit of a joke. Most of my employees had never played a text adventure game and I though they would enjoy it. I told my wife about doing this and she said ‘oh, you’re such a geek boss.’ True story.)

MUD (Multi-User Dungeon)

A MUD is a text-only adventure game which allows many people to explore at once. It was arguably the first massively multiplayer online game.

I played a MUD briefly at university but got regularly slaughtered by super-players and got a bit fed up with it. However, when I was a teenager these were the games I dreamed about creating.

The original MUD was written in 1979 by Roy Trubshaw, an undergraduate at Essex University and when he finished his degree and moved on Richard Bartle took over. The first external players arrived in 1980. In Bartle’s website there is the interesting comment “The first external wizard was Jez [San], who in those days was just an enthusiastic schoolkid, but now runs his own computer games company.”

The game has evolved, spawned and is still running today. It is also the evolutionary source of games like World of Warcraft and the others.

- Play the original MUD

- There are lots of newer MUD type games out there, just Google

The Hobbit

I couldn’t talk about adventure games without mentioning the Hobbit.

Developed by Philip Mitchell and Veronika Megler in 1982. It achieved 1m sales which probably makes it the best-selling single adventure game ever. First developed for TRS-80 but ported. The first Spectrum version was called 1.1 to make it seem more complete.

Unusually, it used a licence well – adapting it to fit the style of game and to to create characters, settings and expectations but without spelling out how to solve the puzzles (in fact the book was given away with the game). I haven’t researched this, but I wonder if it was the first licence game.

It used simple graphics to show locations to the player. It had a good parser which allowed limited communication with NPCs as well as complex sentences. Above all, it was also well-executed and fun.

I want to leap ahead by about 12 years to the point where I think that adventure games died

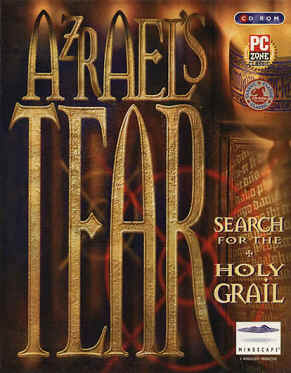

Azrael’s Tear

You’ll forgive me if I mention one game that I worked on in this article.

Of the twenty-plus computer games I produced, it was the game I was most proud of but I think it marked the end of the road for the adventure game.

Interestingly, it’s the only game we’ve done that got fan mail. It was developed by Intelligent Games and published by Mindscape in 1996. Designers: Ken Haywood and Richard Guy. Lead programming Philip Veale and lead art by Richard Evans.

Hands up everyone who played it? Who even heard of it? [Very few people have.]

You probably haven’t heard of it and you definitely won’t have heard of its unpublished sequel Dark Hermetic Order. Ironically, it was also the hardest game to find a playable version. My PC will emulate a BBC, a Spectrum, an Atari 800, even a PDP-1 but I can’t get it to run a DOS game anymore!

It did some things really well: use of music, speech and sound effects; creating a 3D environment and solving the problems of creating an adventure game in it (DHO was even better with its scripting language), creating an thoroughly-imagined and detailed world. But, it didn’t sell and the sequel was cancelled. I expect there have been some, but I struggle to recall any adventure games since AT – except perhaps Blade Runner which had many virtues but also stiffed.

Anatomy a successful failure

So what went wrong?

- Simply updating an existing genre (e.g. text adventures) with new technology (e.g. 3D graphics) doesn’t work.

- User interface and learning curve matter a lot – there’s no point having a great storyline if nobody gets to see it.

- Programmers work in darkened rooms, give the user a brightness control / gamma correction.

- It was for the wrong platform (DOS) at the wrong time (when Quake came out and when Tomb Raider was first appearing)

- Stupid name

- It ran really slowly – creating the sort of luscious 3D environments we wanted – it was originally intended to be a Myst-style pre-rendered game – required a lot of polygons.

But I think the biggest problem was one of sentiment. The audience had disappeared – people didn’t want a puzzle adventure game dressed up in 3D. Quake and Tomb Raider simply provided more bang per buck. I do sometimes wonder whether the immersive storytelling that happened in AT and its predecessors can be evoked somewhere else, perhaps to replace the nonsense of FMV segue sequences. Perhaps instead of puzzles, the player can make character or plot choices? We mustn’t let ourselves forget about story, emotion, character and setting.

Azrael’s Tear is the hardest game in this history to find and play. There was a Windows version but no Windows demo. The DOS demo still works but is very hard to track down on the web.

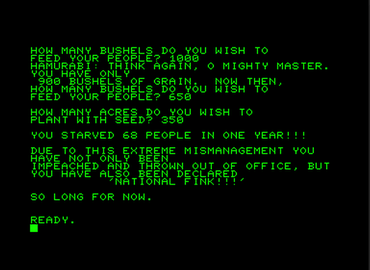

Hammurabi

Another early game, sometimes called Hammurabi, sometimes called Kingdom, was fifty lines of BASIC code that crudely simulated a feudal domain. The game ran in yearlong cycles, and for each year you would tell it how many acres of grain you wanted to plant, what your tax rate was going to be, and a few authoritarian central planning fiats.

I first encountered the game around 1980 – before I even had a computer – in a book called “Basic Computer Games” by David Ahl, who was editor of Creative Computing. Other people may remember a similar game from the BBC Micro Welcome Pack.

I think this genre appeals because: 1) we’re all egomaniacs who think we can do a better job than our bosses and 2) because it is based on a model or approximation of the real world and we all think we know how that works; so like Pong, we don’t need a lot of training to understand the game mechanics.

These aspects: 1) vicarious experience and 2) real-world modelling are important to a whole genre of games that includes driving, fighting and flight simulation and the games I am looking at here.

There is an online version.

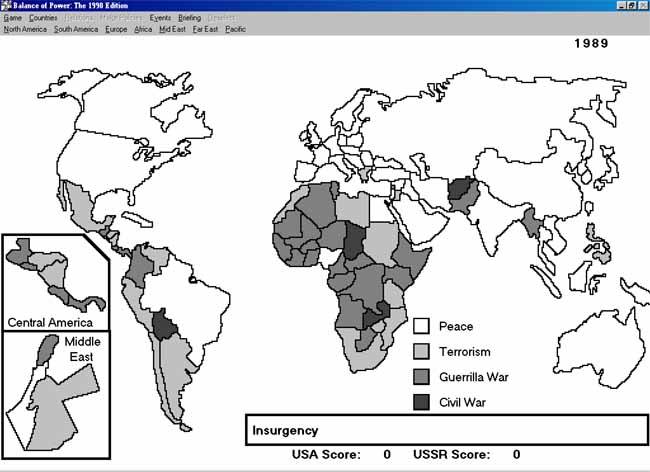

Balance of Power

In 1988, Chris Crawford wrote a game called Balance of Power.

I had this game and I also read the book he wrote about developing it. Chris remains one of the foremost thinkers about interactive design and his website has a lot of useful material and you can find copies of his book on game design on the web.

The player controls either the USSR or the USA and the object is to maximise your influence while avoiding global thermonuclear war. Sounds like fun! In actual fact, it is – and thought-provoking. It sold about 250,000 units.

However, I think that the game shows that the sheer originality of the subject, however well-executed, doesn’t make for a great game on its own. I think the big hook in the game was gambling – how close to the edge could you go without blowing everything up but the game lacked pizzazz and spontaneity and its successors: Guns and Butter and Balance of the Planet were dire and didn’t even have nuclear bombs.

In my idle moments, I still dream of doing a new version of this game but I get laughed at whenever I suggest it.

Play Balance of Power on a Mac emulator in your browser.

Which brings us to another game that got laughed at by every publisher who saw it…

SimCity

Because SimCity was rejected by every publisher he showed it to, designer Will Wright and his friend Jeff Braun got together and founded Maxis to publish the game themselves in 1989. SimCity Classic, 2000 and 3000 have sold a gigantic number – well in excess of six million copies. Of all the computer games I have played, I think this one left the deepest impression on me.

When it came out, it looked very different. The isometric graphics and scrolling map were innovative. Populous had done the potty time people thing pretty well but I think SimCity was the first game to evoke a genuine feeling of ownership and creativity. It’s my city and I’ll build if I want to. It took four years to develop. It is a work of passion and conviction. It was endlessly refined and polished.

SimSpinoffs

Few of its spin-offs sold as well, although I got royalty cheques for SimIsle which we developed for Maxis in the early nineties, and I think the reason is that any game is a creative response to its subject matter. What works for cities may not work for Jungles and definitely doesn’t work for Ant Farms. I think this is an important lesson for marketing folks.

- You can have any two of fast, cheap or great; but not all three.

- If a genius presents a great game, sign it. I bet there are a lot of people who feel like they turned down the Beatles now

- Cloning a game concept without adding anything is going to produce rapidly diminishing returns

Ironically, in a cruel twist of fate, even Maxis made this mistake. In an interview in 1984, Will said: “I have in mind a game I want to call “Doll House.” It gives grown-ups some tools to design what is basically a doll house. But a doll house for adults may not be very marketable.” I saw an early prototype at about the same time and this game eventually became The Sims. Rumour has it that Maxis’s own board rejected the game when he pitched it to them.

Lastly, Will’s a very thoughtful and man and I wanted to give you a flavour. My favourite Will Wright quote: “”What I like about The Sims is that after playing it for a while, you realize how much of your actual life is a real-time strategy game.””

From Hammurabi through SimCity we get games like Theme This, Tycoon That and Sim Whatever, including the game I designed: SimIsle.

Play SimCity Classic in your browser

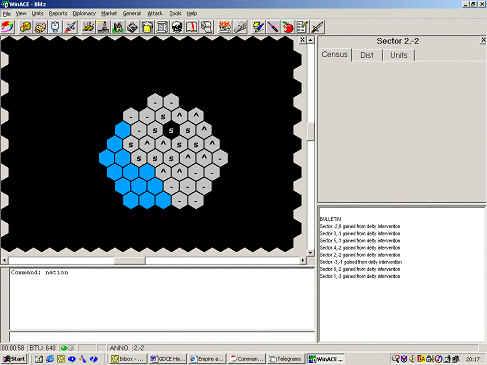

Empire

Just as Space War is a the grand-daddy of action games, Empire is the ancestor of strategy games. It was originally developed at the Evergreen State College in Olympia Washington in 1973 on an HP2000C computer.

You thought Civ 2 was complicated – try Empire. There’s a reason this was written by Phd students!

I played Empire Deluxe on a Mac in the late eighties. Looking back on it, it seemed like an early version of Civilisation. You had tanks, ships, aircraft, carriers and so on moving about on a gridded map of islands.

Ur-Civilisation

It has all the aspects of games like Civilisation:

- Interaction between economics and military production

- It has a shroud which hides unseen terrain

- Alliances and diplomacy

- Above all, the game play consists of a perhaps one or two dozen basic actions applied repetitively to achieve long term aims

Between the late sixties and mid-seventies the PLATO project, a multi-user educational system then under development at the University of Illinois, was the nursery of a number of new technology developments including advanced bitmap graphics massively multiuser connectivity.

Many people, including Chris Crawford who was a programmer there, developed games including a 3D star trek game, adventure, Empire and tank and flight sims that were ahead of their time. In 1977, PLATO put on line the first tank simulator (Panzer Plato). This game was done for the US Army Armor School at Fort Knox and was quite detailed and accurate. At the same time, Chris Crawford published the first computer war game – Tanktics – on the Commodore Pet. His next wargame…

Eastern Front

Eastern Front is an important milestone. For me personally, it was probably the game I liked most when I was a teenager and made me want to design games rather than just play them. I don’t think it had a deep impact on the industry because of its subject, but it is a forgotten classic.

- Simple UI – joystick, start button and space button only

- Push-scrolled map

- Visual feedback of orders given

- Special effects: colour, flashes, scenery changes in different seasons

- Use of sound and graphics for UI feedback and results feedback

- Almost no stats and no rules to remember

It’s an example of how new technology and careful UI design can transform a complicated, dull activity (playing a paper wargame) into entertainment.

Chris said in his 1980 design diary: “Mostly, I thought about what it would be like to play the game. What will go through the head of a person playing my game? What will the person experience? What will he think and feel?” For me this is one of the most important lessons from this talk. The other is the importance of delight – for the user and the author.

Chris has deposited a huge bundle of documents and files relating to Eastern Front in the Internet Archive. And you can play Eastern Front online in your browser too.

Legionnaire

Chris’s next title was Legionnaire which used the same graphics system and UI to recreate Roman legions fighting barbarians. They key development was that the game was real time. Between these two games, you have most of the ingredients of today’s RTS games.

Lords of Midnight

I loved Mike Singleton’s “Lords of Midnight”, which was published in 1984. It was an innovative attempt to do a grand strategy game with a first person perspective. I wonder whether there’s room to develop this concept now we have much better 3D graphics?

Dune II

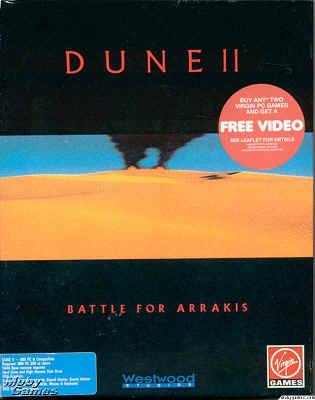

Published in 1992 by Virgin and developed by Westwood Studios.

Full disclosure: IG developed Dune 2000 and Emperor: Battle for Dune for Westwood, so I am probably biased.

It is often credited with starting the RTS genre and I think it did in practice; but some credit has to go to Chris Crawford’s work, Stonk on the Spectrum and Herzog Zwei on the Sega Megadrive; which all contained some genre elements.

This is what Brett Sperry said about the conception of Dune II:

“The challenge was that strategy games would be out-of-control fun if the real-time aspect of Eye of the Beholder could be combined with resource management and a dynamic, flat interface. Just one mode of play and no additional screens. But how? Long before I decided to experiment with actually building this new game in a Dune setting, I kept toying with the answer.”

Real-time strategy

Like Empire, it used a limited number of simple rules which could be combined into complex strategies but It’s telling that the design started with an aesthetic and UI consideration.

It is clearly influenced by the WIMP interface that was beginning to appear on Macs and Windows at the very end of the eighties. It used a scrolling window, mouse select, and buttons but NOT selection marquees. Other innovations included:

- It was real time

- Pictures of units not symbols

- Visual feedback, like bullets, craters, wheel tracks and so on

- Enemy AI to allow solo play (I think this is often overlooked because later C&C became so MP focused)

- An invention tree

It seems to me that almost all of these developments are based on making the game more accessible.

From Empire and its descendants, today we have the whole family of turn-based strategy games, like Civilisation, and all the realtime strategy games; which brings us right up to date. The latest (and best, at least in my opinion since I worked on it) is Emperor: Battle for Dune which came out a few months ago.

Computer games: the past is prologue

My main recommendation is that you take the time to explore old games. Every game I have mentioned today is available free on the Internet. There are links in the transcript on my website. I found it hugely entertaining. Also nostalgic. It reminded me about my own history – why I got into the games industry and a little bit why I got out. It’s nice to know that the industry has a history and that we are part of such a passionate and creative tradition.

The challenges of classification

Coming at this as a historian rather than a practitioner, it is interesting to see how games are classified and how they evolve. It is interesting to see turning points as one genre dies and another is born. It is fascinating to see how today’s developer faces problems that are similar to those faced by pioneers, even though games have increased in size twenty or thirty-fold in the last ten years. It’s interesting to see that there is rarely such a thing as a completely original idea: generally people evolve ideas and apply them to new situations and exploit new technology. There seems to be an informal canon of ‘great games’ but no real rigour has been applied to either the history of computer games or their classification and analysis. At this point I will use the academics cop-out: more work is required to explore these themes.

In conclusion, as the man said: “those who forget their history are condemned to repeat it.” So I look forward to giving the same lecture this time next year. Thank you.

(As it happened, I don’t think I did ever speak at this conference again but I did end up doing a lot of research into the history of computer games for the Wired infographic and for a book that I was researching but never wrote.)

.jpg?width=800&height=500&name=andrew-m-d4Bk6VRyfXo-unsplash%20(1).jpg)